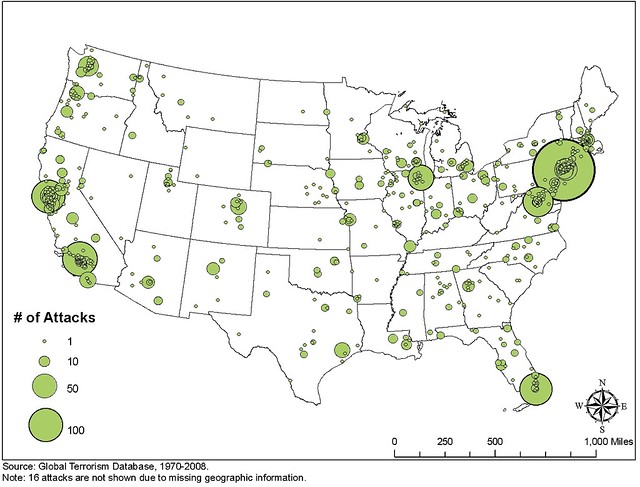

Nearly a third of all terrorist attacks from 1970 to 2008 occurred in just five metropolitan U.S. counties, but events continue to occur in rural areas, spurred on by domestic actors, according to a report published today by researchers in the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), a Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Center of Excellence based at the University of Maryland.

The research was conducted at Maryland and the University of Massachusetts-Boston. The largest number of events clustered around major cities -- in Manhattan (343 attacks), followed by Los Angeles County, Calif. (156 attacks), Miami-Dade County, Fla. (103 attacks), San Francisco County, Calif. (99 attacks) and Washington, D.C. (79 attacks).

While large, urban counties such as Manhattan and Los Angeles have remained hot spots of terrorist activities across decades, the START researchers discovered that smaller, more rural counties such as Maricopa County, Ariz. - which includes Phoenix - have emerged as hot spots in recent years as domestic terrorism there has increased.

The START researchers defined a "hot spot" as a county experiencing a greater than the average number of terrorist attacks - more than six attacks across the entire time period of 1970 to 2008.Sixty-five of 3,143 U.S. counties as hot spots.

"Mainly, terror attacks have been a problem in the bigger cities, but rural areas are not exempt," said Gary LaFree, director of START and lead author of the new report. "The main attacks driving Maricopa into recent hot spot status are the actions of radical environmental groups, especially the Coalition to Save the Preserves. So, despite the clustering of attacks in certain regions, it is also clear that hot spots are dispersed throughout the country and include places as geographically diverse as counties in Arizona, Massachusetts, Nebraska and Texas."

LaFree, a professor of criminology at the University of Maryland, and his co-author Bianca Bersani, assistant professor of sociology at the University of Massachusetts-Boston, also assessed whether certain counties were more prone to a particular type of terrorist attack.

LaFree, a professor of criminology at the University of Maryland, and his co-author Bianca Bersani, assistant professor of sociology at the University of Massachusetts-Boston, also assessed whether certain counties were more prone to a particular type of terrorist attack.

They found that while a few counties experienced multiple types of terrorist attacks, most counties experienced terrorist attacks motivated by a single ideological type.

For example, Lubbock County, Texas, only experienced extreme right-wing terrorism while the Bronx, New York, only experienced extreme left-wing terrorism. LaFree and Bersani also found time trends in terrorist attacks.

"The 1970s were dominated by extreme left-wing terrorist attacks," Bersani said. "Far left-wing terrorism in the United States is almost entirely limited to the 1970s with few events in the 1980s and virtually no events after that."

Ethno-national/separatist terrorism was concentrated in the 1970s and 1980s, religiously motivated attacks occurred predominantly in the 1980s, extreme right-wing terrorism was concentrated in the 1990s and single issue attacks were dispersed across the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, according to the new report.

To define the ideological motivations, LaFree and Bersani used START's Profiles of Perpetrators of Terrorism, United States (Miller, Smarick and Simone, 2011), which briefly describes ideological motivations as:

- Extreme Right-Wing: groups that believe that one's personal and/or national "way of life" is under attack and is either already lost or that the threat is imminent (for some the threat is from a specific ethnic, racial, or religious group), and believe in the need to be prepared for an attack either by participating in paramilitary preparations and training or survivalism. Groups may also be fiercely nationalistic (as opposed to universal and international in orientation), anti-global, suspicious of centralized federal authority, reverent of individual liberty, and believe in conspiracy theories that involve grave threat to national sovereignty and/or personal liberty.

- Extreme Left-Wing: groups that want to bring about change through violent revolution rather than through established political processes. This category also includes secular left-wing groups that rely heavily on terrorism to overthrow the capitalist system and either establish "a dictatorship of the proletariat" (Marxist-Leninists) or, much more rarely, a decentralized, non-hierarchical political system (anarchists).

- Religious: groups that seek to smite the purported enemies of God and other evildoers, impose strict religious tenets or laws on society (fundamentalists), forcibly insert religion into the political sphere (e.g., those who seek to politicize religion, such as Christian Reconstructionists and Islamists), and/or bring about Armageddon (apocalyptic millenarian cults; 2010: 17). For example, Jewish Direct Action, Mormon extremist, Jamaat-al-Fuqra, and Covenant, Sword and the Arm of the Lord (CSA) are included in this category.

- Ethno-Nationalist/Separatist: regionally concentrated groups with a history of organized political autonomy with their own state, traditional ruler, or regional government, who are committed to gaining or regaining political independence through any means and who have supported political movements for autonomy at some time since 1945.

- Single Issue: groups or individuals that obsessively focus on very specific or narrowly-defined causes (e.g., anti-abortion, anti-Catholic, anti-nuclear, anti-Castro). This category includes groups from all sides of the political spectrum.

To read LaFree and Bersani's new report "Hot Spots of Terrorism and Other Crimes in the United State, 1970 to 2008," visit http://start.umd.edu/start/publications/research_briefs/LaFree_Bersani_HotSpotsOfUSTerrorism.pdf.

*****UPDATE*****

July 5, 2012 Current articles and postings on the Internet have mischaracterized the conclusions of the START report "Hot Spots of Terrorism and Other Crimes in the United States, 1970 to 2008," which was released in January. To be clear, the National Consortium for Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) does not classify individuals as terrorists or extremists based on ideological perspectives. START and the Global Terrorism Database, on which the Report is based, defines terrorism and terrorist attacks as "the threatened or actual use of illegal force and violence by a non-state actor to attain a political, economic, religious, or social goal through fear, coercion, or intimidation."

The report is based on the key premise that the groups and individuals analyzed have actually carried out or attempted to carry out violent attacks in the United States for any political, social, religious, or economic goal. This is what qualifies them as terrorists, not their ideological orientation. The report then classified the violent perpetrators into ideological categories, including extreme left-wing, extreme right-wing, religious, ethnonationalist/separatist, and single issue. The descriptions of these categories in the report do not suggest that an individual or group with one or more of these characteristics is likely to be a terrorist.

Click here for a detailed response from the report's author, Gary LaFree, director of START.

###

The National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) is supported in part by the Science and Technology Directorate of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security through a Center of Excellence program based at the University of Maryland. START uses state‐of‐the‐art theories, methods and data from the social and behavioral sciences to improve understanding of the origins, dynamics and social and psychological impacts of terrorism. For more information, contact START at infostart@start.umd.edu or visit http://start.umd.edu/. This research was supported by the Science and Technology Directorate of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security through awards made to the START and the first author. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security or START.